Maker Metropolis

/

Photo Credit, Scott London

The most Maker City of any city is without doubt Burning Man, a remote place where nothing exists until its citizens create it — once a year, and for only a week.

Every August, Burning Man rises in Nevada’s barren Black Rock Desert, a thousand square miles of wilderness with no water, no electricity, no services, nothing really but a vast playa (a dried antediluvian lake bed) in one of the most beautiful and harsh environments in America.

It was this stunning blank canvas that initially inspired people to come together to dream up a city where they could follow any whim they wanted to try. A do-it-yourself community fueled by the love, triumph, fun, and failure of creating the world they wanted to live in. It has become a Maker metropolis that real cities are learning from today. Ultimately Burning Man is about place making with the entire city built “by the people, for the people.” This sense of freedom and engagement leads to civic agency that has practical implications for how cities can embrace the spirit of making — and become a maker city.

The community started out organically in 1986 and has evolved into a city imagined and reinvented by its 70,000 participants each year. It’s a metropolis of creatives, Makers, performers, explorers, and inventors with its own post office, airport, radio stations, newspapers, volunteer rangers, a DMV (Department of Mutant Vehicles), and a plethora of large-scale interactive art — with no branded content at all. It is a gift economy where nothing is bought or sold, so participants must be self-reliant and at the same time come together to learn, create, and thrive. When the event is over, the whole thing vanishes without a trace. Black Rock City, the largest annual Burning Man gathering, is meticulously cleaned up and packed out by all of its participants at the end of the week.

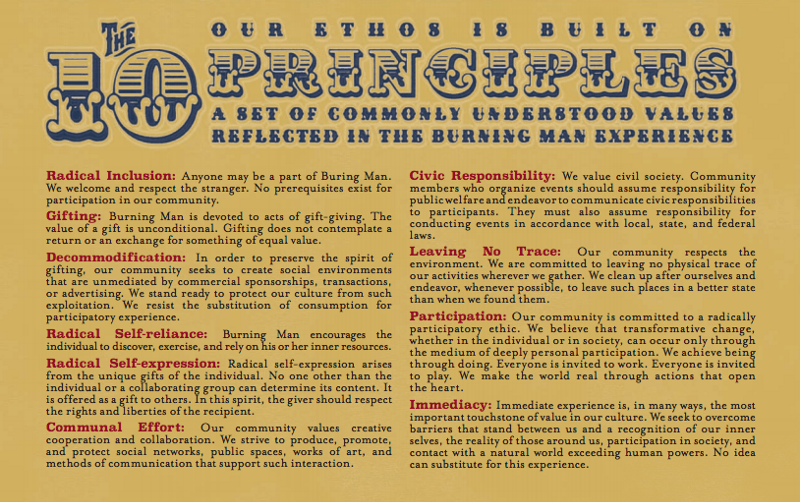

Key Principles of Engagement:

In 2004, Larry Harvey, one of the organization’s Founders, assembled Burning Man’s 10 Principles as a reflection of the community’s ethos and culture to help nurture organic offshoots around the world. In no way prescriptive, these patterns of behaviors serve as guidelines for affiliation and help encourage emergent activity for thousands of participants, theme camps, and art project teams who embrace it as a framework.

In many ways, it’s these principles that provide the permission for social experiments to take place, and for society to be prototyped and re-designed. These principles are often in tension with one another: Radical self-reliance and Radical self expression are all about the individual. Civic Responsibility and Radical Inclusion are all about the community. It’s this constant interplay between collective governance, individual novelty, and emergent activity that is the scaffolding that makes Burning Man such a creative Maker City.

“Out of nothing, we created everything,” Burning Man Founder, Larry Harvey

Burning Man and the Maker Movement:

The event has received much attention for being a petri dish for new technology and art fueling the Maker Movement. However, Burning Man culture is less about the artifacts and more about the mentality of being a Maker and the values of participation, experimentation, and play, with a point of view that is focused on the art first. Beauty and curiosity are put on the same level as functionality and creations are often burned at the end of the week.

A key principle highlighting the Maker spirit of the city is participation. There are no “observers” at Burning Man. The belief is that to be there and receive gifts everyone must participate. Giving permission to everyone to create makes for a heightened sense of civic responsibility and communal effort. These are ideas that enhance any city.

How the City Works:

Preparations for Burning Man take months and involve scores of volunteers, who work together to create the different camps or neighborhoods where people will live as well as the large-scale and interactive public artwork that will decorate the desert floor.

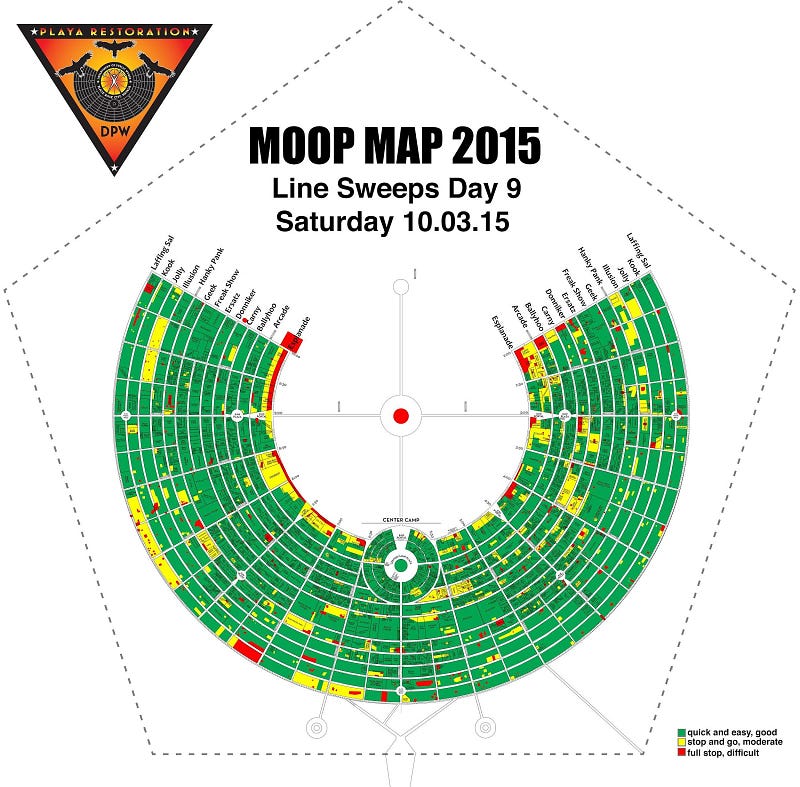

The principle of Civic Participation is furthered by the principle of “leave no trace” — nothing on the desert floor when you arrived; leave it that way. As in real cities, Burning Man uses data and maps to monitor all this. Volunteers develop a “Matter Out Of Place (MOOP) Map” which helps to grade camps on how well they remove traces of anything. This is an example of data about the community being used to drive appropriate behavior.

No cars are allowed inside Black Rock City.

Instead, roving works of art double as public transport. These “Mutant Vehicles” take people around the inner ring of Black Rock City as well as into the City Center. Every year, Mutant Vehicles get more elaborate and ambitious and require ever greater feats of engineering and imagination.

El Pulpo Mecanico was built in Arcata California, Humboldt County. Designed and built by Duane Flatmo along with his friend Jerry Kunkel who masterminded the electrical systems and flame effects. Photo Credit, Scott London.

http://www.cnn.com/2016/09/06/autos/burning-mans-mutant-vehicles/

Black Rock City is Designed in a Radial Fashion

At the center of the radius is “the Man,” an iconic sculpture which can tower 100 feet and is burned in ceremonial fashion on the last night of the week-long festival. Streets are mapped out only from 10:00 to 2:00, leaving open space for views of the mountains and to create lines of sight to the “Playa,” where most of the large-scale art is located.

At 6:00 on the map, you’ll find downtown, the heart of the city known as Center Camp, a 45,000-square-foot shaded structure informed by one of the most important influential models of civic design, the Italian Piazza. This comfortable gathering place encourages chance meetings, deep conversations, and new ideas — much like the historical cafe culture that has given birth to everything from existentialism to beat poetry. It is extremely important to have this feature of urban life, this “third space,” as a special meeting and social hub, at Black Rock City.

Photo Credit, Brad Templeton

http://pic.templetons.com/brad/photo/

“The city’s design helps maintain the sense of expansive, infinite possibility that is natural to the landscape, and also encourages people to voyage out and discover new things. Everyone is attracted to the center and makes their pilgrimage to the Man,” says Burning Man Co-Founder Harley Dubois, making random collisions inevitable and part of the flow. Serendipity is literally part of the “way” here.

Photo Credit, Duncan Rawlinson

https://www.flickr.com/photos/thelastminute/15292883695

The Growth of the Movement:

Burning Man culture has expanded worldwide with 270 volunteer regional representatives who mentor the community in 35 countries and 130 cities and towns. These communities, embedded in American and global communities, are a significant source of inspiration, volunteer capacity, and Maker know-how.

This year’s Burning Japan was held at Iwafune-san, a rock quarry dating back to the Edo era. Photo Credit, Kiruke.

People take the immediacy and civic responsibility home with them. Building Burning Man gives people a sense of their own agency and makes it clear how radical self-expression and civic engagement ultimately leads to a better life. It’s this civic pride — a more engaged form of citizenship not just in Black Rock City but in the real world — that underlies the global voluntary association and network of social trust known as the “Burner” community.

Emergent Activity in the World

David Best, for example, is famous for creating architecturally elaborate temporary temples across the globe. He never imagined that what began as an experiment in the desert would become a worldwide phenomenon. As a result of his initial structure at Burning Man in 2000, the Temple is now a permanent installation built by different guilds, volunteers, and collaborators who submit proposals of their interpretation for what a Temple might be. Being selected to build the temple is a high honour; it has helped many new talents establish themselves internationally.

Photo Credit, Scott London Burning Man 2014, Temple of Grace

In 2015, the Artichoke Foundation commissioned David Best to work with the community of Derry, Northern Ireland to build a Temple on a remote hilltop overlooking the city. The project was designed to unite the community, celebrate togetherness, and help citizens and residents of Derry heal from its traumatic history of conflict. In California, the Temple build crew trained and worked with local students and adults who completed apprenticeships and participated in the build with support from local Fablabs — a form of apprenticeship and skills training.

Photo Credit, Artichoke Trust

Burning Man’s Civic Arm

Burners have also put their Maker skills to use healing communities through an organization called “Burners without Borders” (BWB). Begun as a response to Hurricane Katrina, volunteers with Burners without Borders provided over $1 million worth of reconstruction and debris removal over an eight-month period.

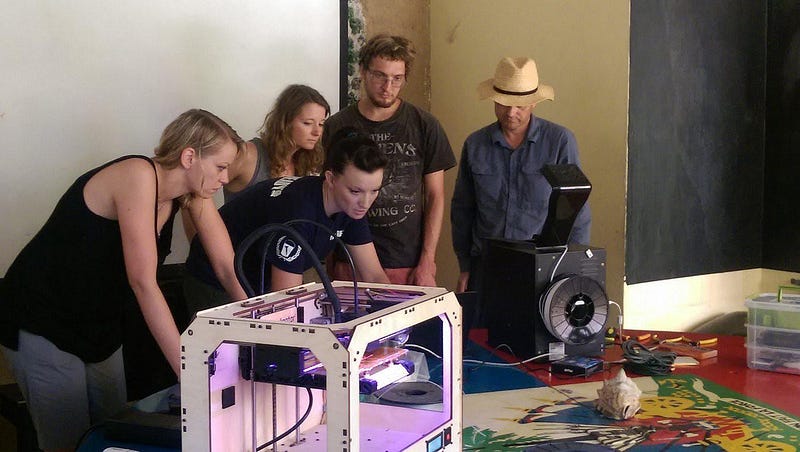

Burners without Borders spawns new projects each year. One shining example is Communitere, a dynamic and sustainable organization that provides Makerspaces to communities that have suffered from natural disasters. This allows people to create the relief efforts they need for themselves, tapping into their own skills and resiliency and applying their knowledge of what they and their neighbors actually need right now. Communitere now operates in Haiti, Nepal, and the Philippines, providing space to NGOs like Field Ready, who is pioneering the use of 3D printers in disaster areas.

Field Ready training volunteers at Haiti Communitere in Haiti 2015. Photo Credit, Fieldready.org

Lessons for the Maker City

Burning Man has been called a “permission engine” that allows for both radical individual expression and rich community collaboration. It’s a construct built on trust and shared values that allows its constituents to create all the facets of the city they want to live in.

The 2016 theme for Burning Man was “Da Vinci’s Workshop,” inspired by the Italian Renaissance when an historic convergence of inspired artistry, technical innovation, and enlightened patronage launched Europe out of medievalism and into modernity. The era was known as “The Age of Discovery,” when the ideas of da Vinci, Michaelangelo. Copernicus, and Columbus reimagined education, production, science, and politics. Like today it was an era of fundamental reframing. Renaissance workshops were forerunners of today’s Maker and innovation spaces — a breeding ground for new ideas that also helped them become reality. Ateliers were established in the Renaissance and saw participatory and vocational knowledge as the core of value creation. In the safe environment of the atelier, established artisans could spot and mentor new budding talent and ideas — networking them together across disciplines, thus fostering new potentials. The ateliers’ major themes resonate with the innovation economy today: turning ideas into action, cross pollinating art and science, and unleashing human imagination.

Photo Credit, Galen Oakes

https://www.fest300.com/magazine/burning-man-photos-2016

The Burning Man Project

Rooted in the values expressed by the Ten Principles, this culture is manifested around the globe through art, communal effort, and innumerable individual acts of self-expression.

As a newly formed nonprofit organization, the Burning Man Project is focusing on offering artists, changemakers, cities, nonprofits, and civic activations a path to becoming agents of change to manifest new ideas in the world.

Participating in Black Rock City or other regional Burning Man events is just one way to get involved with the community. Wherever you are and whatever your skills, there are plenty of exciting opportunities to volunteer, collaborate, submit ideas, and get involved with the global efforts of the Burning Man Network via Burningman.org

Jenn Sander is the Global Initiatives Advisor, Burning Man Project